Blog

Blog

July, 2021

As a fund of funds and a secondary fund that has invested in 244 funds and 103 GPs across the U.S., Europe, Canada and Israel, since 2005 (you can always find our portfolio funds here), we have seen all types of fund sizes, strategies, theses, etc., but at the end of the day, all funds have the same goal – to outperform their competitors and to return as much money as possible to LPs as fast as possible. In today’s frothy VC environment, we are seeing our portfolio funds announce new unicorns[efn_note]Unicorns = a private company with a valuation of $1 billion or more.[/efn_note] and even decacorns[efn_note]Decacorn = a private company with a valuation of $10 billion or more.[/efn_note] multiple times per week, creating massive write-ups in our portfolios. And while we are also seeing increased distributions with the IPO markets open, much of the value still remains on paper and sometimes it seems GPs forget that DPI[efn_note]DPI = Distributions/Paid-In (The amount of capital the fund has distributed to its LPs divided by the amount of capital calls paid by the LPs).[/efn_note], and not just TVPI[efn_note]TVPI = Total-Value/Paid-In (Distributions plus Remaining on paper value divided by the amount capital calls paid by the LPs).[/efn_note], matters.

First, to “set the table”, we took a sample from our database of roughly two dozen funds of top U.S. and European VCs from vintage years[efn_note]Vintage year = the year that the fund was legally established – using the Cambridge Associates Benchmark definition.[/efn_note] 2006-2011 – i.e. funds mature enough to have had meaningful exits, but at the same time still with a number of active companies left in the portfolio – and looked at how much of the value was yielded by how many companies.

Overall, 65% of the portfolio value was yielded by 10% of companies, with a number of the funds having 80-90% of the value yielded by 10% of the companies. This is not surprising given that VC is an outlier business – it is about elephant hunting where a few huge winners generate the majority of returns. We actually expect the contribution of the 10% to grow over time (e.g. to 75%+) as the remaining companies continue to grow in size.

Clearly, VCs should be focused on cultivating this 10% – identifying them early, allocating reserves, nurturing, doubling down, and maximizing value by holding them long-term[efn_note]Of course, in today’s frothy environment, we do advocate that funds take advantage of private rounds to sell a portion of their holdings if the return can have a meaningful impact on the fund while keeping a meaningful portion on the table, but ultimately we believe the winners should be held.[/efn_note].

But, what about the other 90% of the companies that yield a minority of the value? GPs have a few assets – their money and their time are the two that are the most in-demand. By holding onto this 90% of the companies instead of turning lemons into lemonade as early as possible before any value, they may actually have degraded. No less important, the GPs spend valuable time on these companies, instead of investing the time on making the big winners into huge winners. Either way, selling off the moderate to low return companies early, not only improves DPI but also IRR; the impact on IRR of getting to a DPI of one quickly is huge.

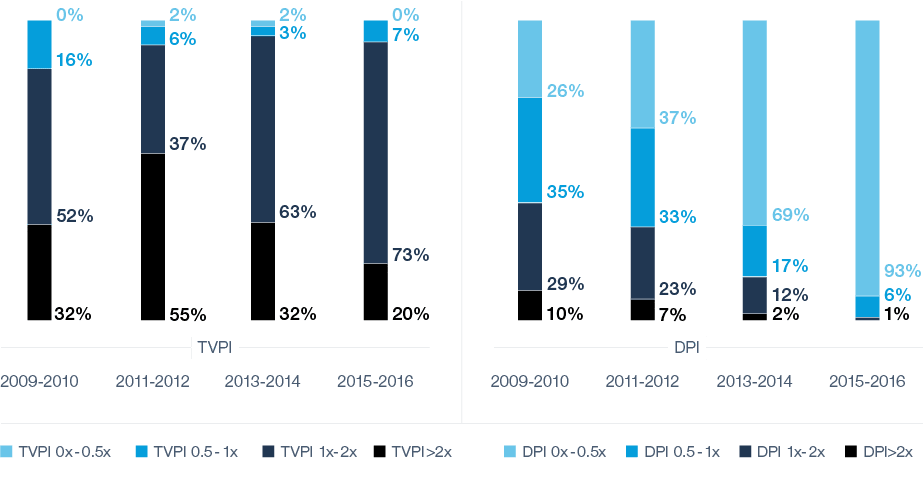

Next, we dove again into our database of VC fund returns and looked at >200 VC funds from vintages 2009-2016, across the U.S., Israel, Canada and Europe, to see how many funds actually returned their capital called (i.e. a DPI of 1x or more) compared to their TVPI (Figure 1).

When looking at 8-10-year-old funds, nearly 55% of the funds returned over 2x TVPI and have meaningful value remaining, but at the same time, when looking at distributions, only 40% (less than half!) have actually distributed more than 1x the capital LPs invested.

Figure 1 – 2009-2016 VC Funds DPI and TVPI

When combining these three figures – that 10% of companies yielded 65% of returns (and again in many cases much more than 65%), the high TVPIs, but much lower DPIs – it seems to paint the picture that GPs are probably holding onto their winners/outliers/elephants (which is great), but perhaps not extracting enough value as early as possible from the rest of the portfolio – which can make a bigger difference than one thinks.

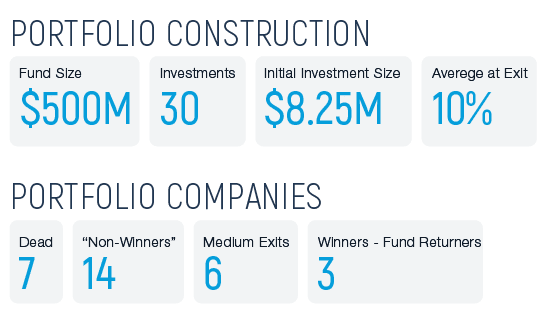

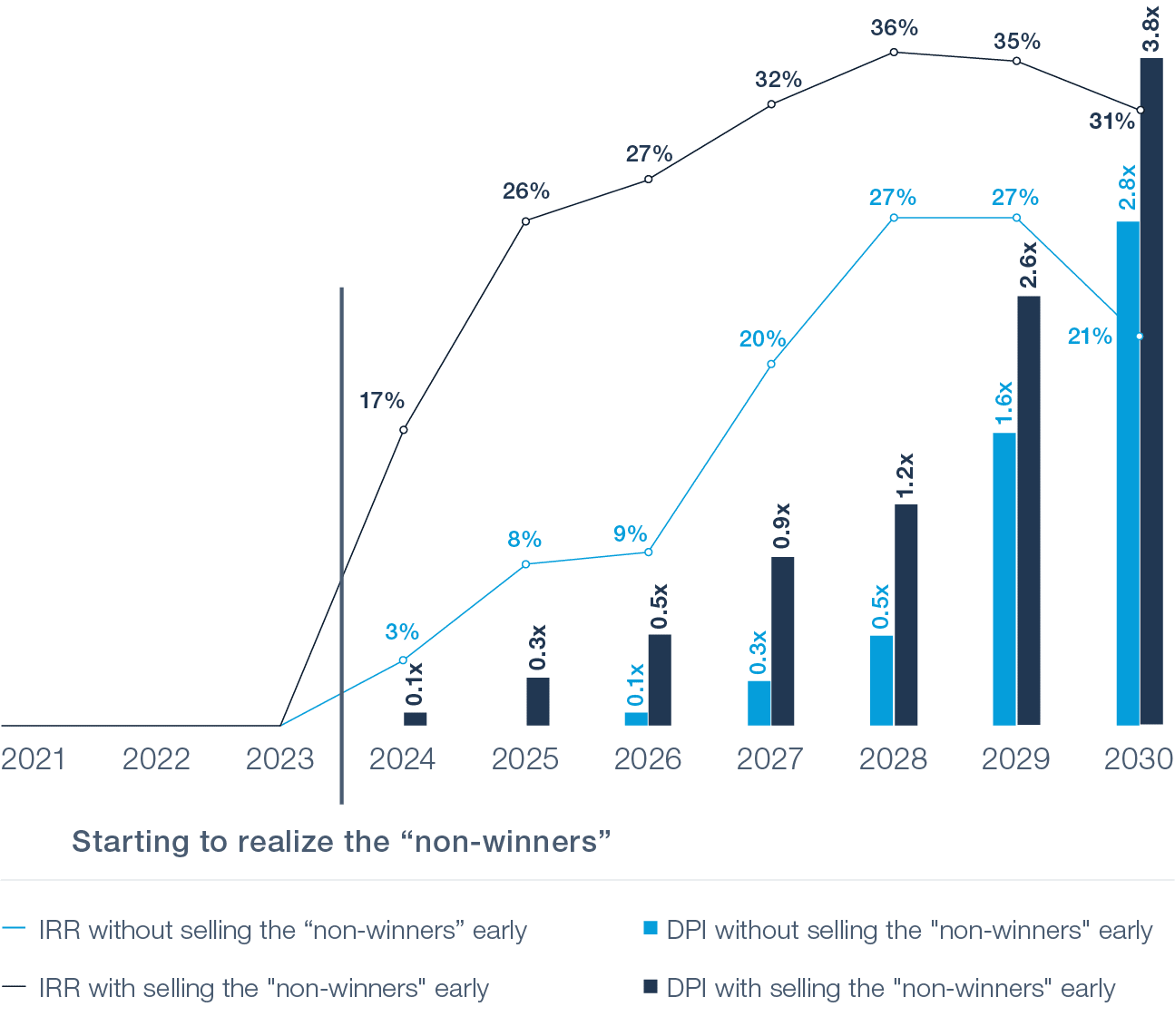

To help visualize this, we compared two “virtual” funds of $500 million, invested in 30 portfolio companies – one which had early realizations and one which didn’t – and tracked the IRR and DPI to see the effects of realizing the “non-winners” early (Figure 2).

Fund 1 begins to realize some of the companies after four years. This is when the fund managers should be able to identify many of the “non-winners”, but to potential buyers, these companies may still hold value as the “vision” part of their story still resonates versus the actual business results. In contrast, Fund 2 waits two more years to realize them and ultimately their potential value diminishes.

Figure 2 – Demo Fund

Assumptions:

As you can see the early realizations not only boost the IRR (and of course the DPI), but the future IRR decline will be less deep as the IRR is more “locked-in” given the early exits. Ultimately our virtual Fund 1 does one extra turn on the fund and generates 1000 more basis points in IRR – pretty significant!

While most GPs (and LPs) will say the 2 (or 3) key venture skills are Sourcing, Accessing, and perhaps Building, it begs the question: What about the skill of Exiting, especially the companies that are not obvious IPO candidates?

We have seen different approaches to improve the “exiting-muscle”. First, starting with regular, honest midterm assessments of each portfolio company – is this still a team that can take it all the way? Can they still be a market leader? Is it too early or too late?, etc. Second, some funds have a team member focused on this function, cultivating relationships with the relevant bankers, buyers at large corporates, PE funds, etc. In fact, we believe a “Banker-in-Residence” should become a key function within a VC fund.

Ultimately, generating liquidity should be added as a key skill set for VCs – knowing how to determine when it is time to sell and making a plan – not sitting idly by and waiting. Clearly, as seen above the importance of realizing the non-winner group early can make the difference between a good fund and a top-performing fund.

“To emphasize the point of the impact of early exits, we have a portfolio fund (a 2017 vintage year seed fund, <$100 million), that is already at a >1x DPI, >4x TVPI, and >200% IRR. But how did they do that so fast? It was not magic (maybe a little luck, but not magic) – they picked and accessed some great companies BUT also had some early realizations. Specifically, thanks to a high holding percentage in one of the companies they assessed as a non-winner and found a home for, they saw a very nice and rapid return without a large absolute exit. The fund also partially realized one of their winning portfolio companies as part of a very large (but early) growth round, while still holding a large portion. Combined, this allowed them to return 1x the fund to its LPs and “lock-in” a lot of IRR for the long run.”